Post-fermented Tea (dark tea)

Post-fermented tea, aka Dark tea 後發酵茶、黑茶

Post-fermentation in tea is one which is brought about by microbe activities — fermentation in the truest sense of the word. This process, similar in broad definition as in the production of vinegar, wine, yogurt or soya sauce etc, causes a dramatic change in the chemical nature of the raw material. As such, this is a most unique tea category both in terms of taste and salutary benefits.

orientation

Prior to the systematic development of the modern method through the 1960’s and 70’s, post-fermentation in tea had been mostly uncontrolled. Microbes in the environment come into contact with semi-processed tealeaves and those with affinity to the raw material grow and multiply to trigger the bio-chemical changes. This darkens the leaves.

Today, this “natural” post-fermentation process in semi-controlled environment is still preferred by some. Depending on the environment and packaging, a tea is turned completely dark only after many years, sometimes many decades.

The modern method, in which leaves are piled up for fermentation in pre-conditioned environment, normally takes 50 to 90 days.

The best known example in this category is Puer (formally Pu’er, aka Po Lei, Puer, Pu-erh). However, other productions, such as Hunan Biancha, Sichuan Zhang Cha (Tibetan Teas), etc are important grocery for a large number of people today and in history.

Ancient style dark teas, such as those from Hunan and Sichuan, are very astringent and bitter. They are meant to be consumed with various kinds of condiments such as goat milk, yogurt, seasonings, nuts and herbs, in the tradition of the nomadic and mountain people in the western part of China and Central Asia, where the lack of vegetable in their diet is remedied with the substances in tea.

A fine modern dark tea is properly post-fermented, stored and matured. It gives a dark burgundy liquor that is transparent, and a woody aroma with hints of ripen hay and herbaceous scents. The taste is sweet, round and deep with light notes of bitterness and astringency. The texture is silky, some even velvety, with after suggestions of grains. Repeated infusion reveals more sweetness.

This is a problematic category involving irregular manufacturing practices, mega-scale price speculations, and dishonest pricing and labeling. There is also the inherent issue for a universal category definition. However, even for all these issues, this is a most special tea category and one that is loved by many. It is a best and most versatile staple tea for food pairing. Finding fine and worthy ones is a true adventure.

Production

Raw materials differ dramatically in this category. Basically leaves of all sizes from a great number of cultivars, some of which are camellia of different varieties, from a few different provinces are used.

Some productions would involve various degrees of enzyme-triggered fermentation before the tea is piled up for post-fermentation. For example, some producers pile up the leaves in thin layers and let wither under the sun. Due to the layering of leaves, it is like a later stage in the making of white tea, when slight enzyme oxidation takes place. Others roast or bake, twist, and partially dry the leaves first as a raw material.

The crude tea, “mao-cha”, as they are called, can be stored to let age through “natural fermentation” as some in the trade like to call it, or can be put through post-fermentation. Details of the practice vary, basically the crude tea is piled to a thickness, some 30 cm, others can be 100 or more, spray with water and let microbes do the job. Some is set to run for 60 days, some less than one. The process is referred to as oudui, or piled-fermentation.

The microbes involved are common fungi such as Saccharomyces, the same type that is the brewing yeast. Aspergillus glaucus, another one which fermentation effects with tea is being studied for the special health effect of pu-er, exist naturally almost anywhere.

A worker covers the pile of tealeaves for another round of fermentation. This is towards the later part of the oudui process for post-fermentation in puer production.

The piles are regularly checked for temperature and the visible condition of microbe activities. Very simple measures such as airing, thinning or thickening of the pile are used as control. The process vary somewhat between producers and regions. People have been disclosing their own processes with limited facts, but according to my observation, the local climate, choice of tea, and the desired effects have much to do with the variations.

Nevertheless, once the microbe finishes its life cycle, or being halted, the tea is taken to another round of twisting and baking. Some producers just dry it.

A significant amount of the production is taken to the next production stream: compressing the tea into a molded form, be it a discus ( cha bing ), a brick, a mushroom, a pellet, a cube, in a bamboo, pomelo, or orange, or any other fancy forms.

Very often the tea thus produced, be it loose leaves or compressed, to be “naturally fermented” or already post-fermented, is sold immediately to dealers, larger “factories”, and wholesalers. They would then sell some and shelf some for maturity. Many re-package them. Since a speculation trend has been going on, price jumps according to length of storage. Better traders would honestly label the properly shelved lots for production year and maturity record. Others just pile it up in some corner of their warehouse and give them a maturity year as they improvise when selling the lot.

Tasting notes

Dark tea, wherever it originates, requires a wash with 100°C water to open up for proper infusion. This also rinses the tea of the residuals of microbe on the surface of the leaves, if any. If you are unlucky to have a tea that does not look clean because of storage conditions, blanch it two times. Properly blanched tea tastes less muddled.

A fine dark tea may look quite dark when properly infused, but should taste well balanced with just enough astringency. Some may even be very mellow. Overly astringent taste indicates tea without post-fermentation. If the other qualities of the tea are fine, it may develop through maturing.

Because of the rigourous processing done to the tealeaves in a genuine dark tea, tea contents infuse into the water quite readily. The usual practice for most drinkers is to put in a bit more leaves and infuse for shorter time. here for standards of infusion parameters><Click here for updates for future articles about advanced infusion techniques.>

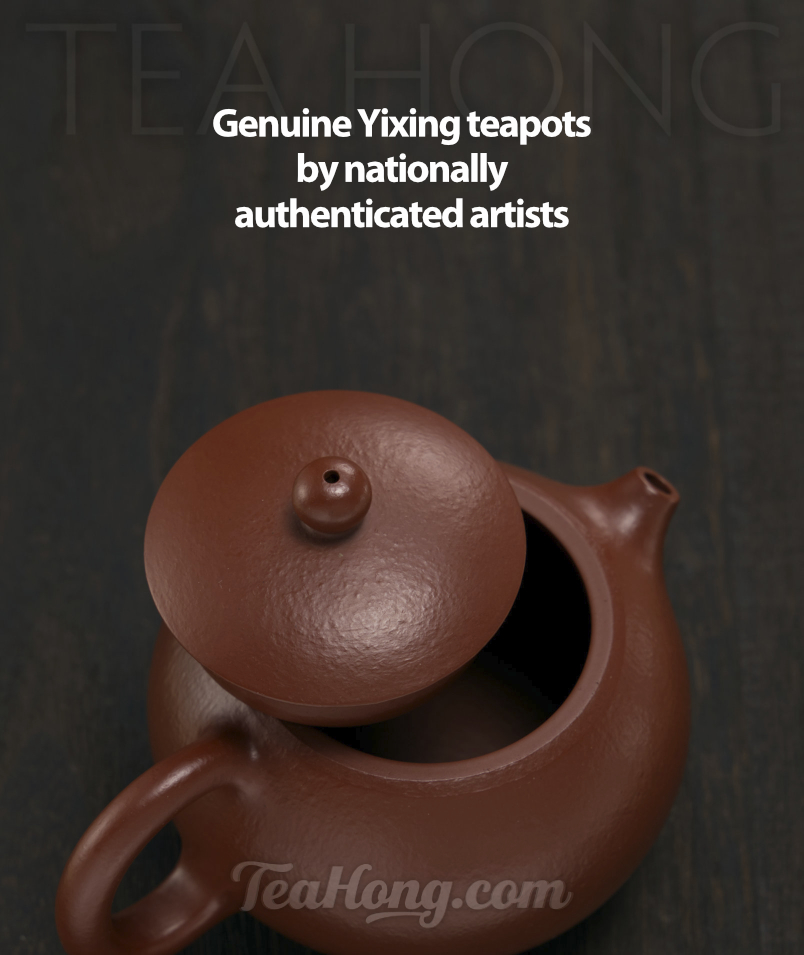

A fine dark tea fares much better in a Yixing teapot, with which you can make a really black, and yet transparent, infusion that is sweet and full of taste.